AFX Advisor Robert Albertson offers his perspective on what lies ahead for the banking sector in 2024.

A Weakening Economy

Economic consensus had only recently centered on a “soft landing” with no recession and Fed rate cuts as soon as 2024. Both are premature conclusions in my view. Some are now suggesting a recession has already begun.

1) Consumer spending is likely to slow, despite its third quarter surge, as monetary restraint has typically taken up to two years to work its way into the economy. This would argue that the full impact from Fed tightening won’t be in place until early 2024. The spending trajectory is still a key uncertainty. The November spending data will be available on December 22nd and will provide a key insight into this trajectory and whether a recession is the likely outcome.

2) Fixed investment continues to be weak and slowing consumption is unlikely to instigate any revival in the near term. Investment spending is a key driver of commercial borrowing.

3) Inflation remains too high. While the Fed is understandably comforted by the decline in inflation to date, headline inflation has much further to fall before reaching anything like the 2% target. While not as far away, further core inflation reduction probably becomes much harder to achieve than its progress to date. The Fed is also prone to keep interest rates higher-for-longer, which has been its mantra all along. While sufficient economic weakness could motivate rate cuts in 2024, the degree of weakness will be important, and the Fed is highly oriented to keeping rates higher-for-longer. The November jobs report suggests rate cuts in 2024 are still very presumptuous.

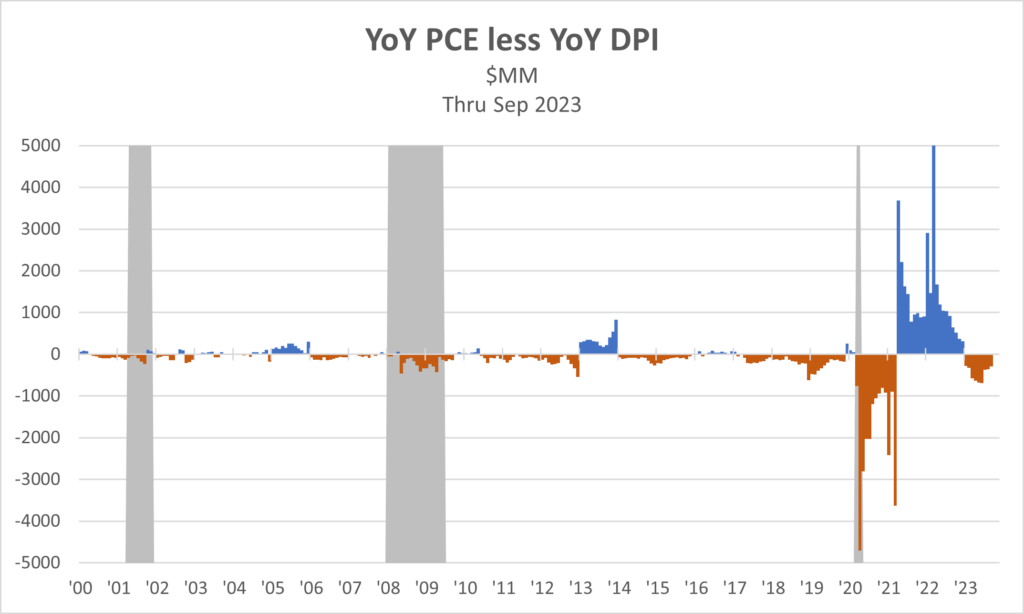

Consumer spending (PCE) is strongly correlated with disposable personal income (DPI.) That was not true, for the first time, during COVID when social distancing wreaked havoc on retail sales, travel and entertainment. It is also well understood that the consumer savings rate soared and government checks were diverted into savings. There are many estimates of this “excess savings” and when it would run out.

But as the exhibit above demonstrates, the excess is already largely gone. Although spending averaged 91-92% of DPI before COVID, spending fell well below income beginning in March 2020 and continued so for 13 months – the period of excess savings. Following this there was a 21-month period when spending dramatically overshot DPI essentially draining excess savings. Beginning in 2023 that abnormal, savings-induced high level of spending effectively ended and spending steadily dropped back to its historical average relationship, slightly below DPI.

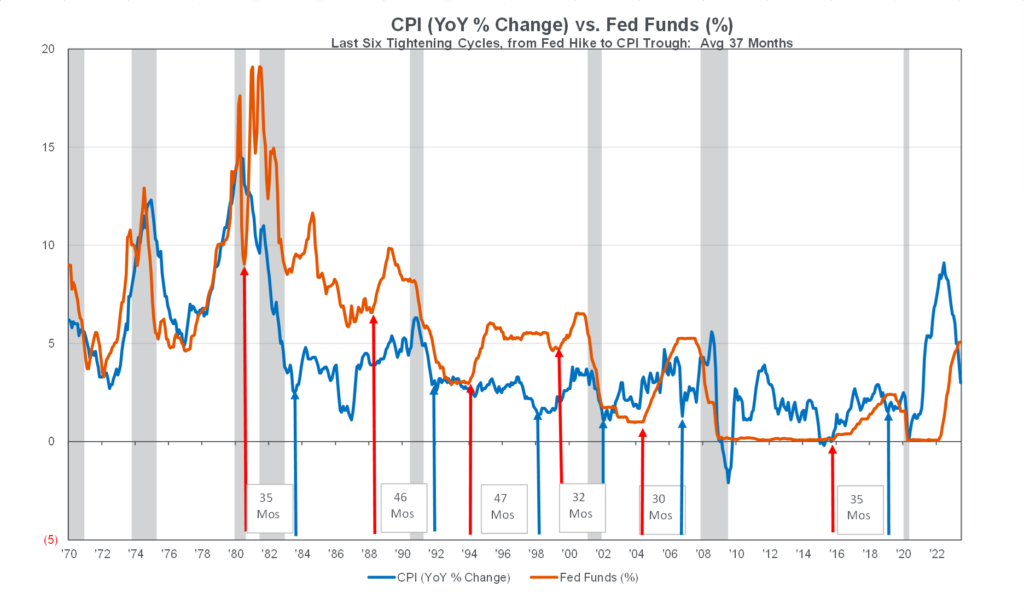

This suggests that consumer spending will gravitate to a level slightly below the pace of personal income growth going forward. DPI growth has been steadily decelerating all this year, from 9% down to 7% in nominal terms in October, implying real growth of 3% currently. Assuming job growth returns to decline, which is key to the Fed’s monetary policy stance, real consumption is likely to fall to a 1-2% pace at best in coming months, which is clearly weak, and uncomfortably close to either stagnation or a mild recession. It is still too early to know. The following exhibit attempts to quantify the historical lag from a rising Fed Funds rate to a subsequent bottom in inflation. The average lag over the last six episodes is a little over three years.

This would suggest an inflation bottom toward the middle of 2025, which is roughly consistent with the Fed’s latest (September) Summary of Economic Projections (aka the Dot Plot.) This same SEP projected a 2024 Fed Funds rate median of 5.1%, which had been revised up by 50 basis points from the previous SEP, signaling a lengthening shift in timing, that may well be extended. While this supports a best guess rate cut in the latter half of 2024 it will be entirely contingent on steady inflation data improvement and slower economic momentum in general, and a clear descent in jobs growth and wage rate. There are as many as six rate cuts projected by some in 2024, which seems an unrealistic outcome at this time.

Employment is the biggest determinant for both the Fed’s stance and the general economy. The latest November jobs data of 199,000 was above estimates but included the benefit of two strikes coming to an end. However, the Household Survey, which excludes this dynamic, was extraordinarily strong. The biggest surprise was that the unemployment rate went down further to only 3.7% from 3.9% in October. The Fed has repeatedly said it needs to see higher unemployment before considering any relief from high rates. Average hourly wages also went the wrong way, with a month-over-month gain of 0.4%, up from 0.2% in October. The labor market is NOT suggesting a Fed pivot to lower rates at this juncture.

Important Challenges for Banking

We offer six for primary consideration:

1) A slowing economy will further deteriorate loan demand, the principal source of revenues for all but the largest of banks. Loan growth was already muted in the recent (third) quarter, primarily due to further softening in commercial and industrial borrowing demand along with bank reluctance to expand in commercial real estate. Managements also cited customer caution driving this softer demand. Only credit card borrowing remains strong and was characterized as merely “normalizing.” Virtually all recognize that the economy and the course of interest rates will define future loan growth, but at this juncture ongoing weakness seems almost certain.

2) Net interest margin pressure will return when, and if, rates decline. Most banks are still asset sensitive in the short term albeit many are hedging against this eventuality. Net interest margins were mostly down in the latest quarter and are likely to continue their slow erosion as higher-for-longer interest rates drive deposit betas inexorably higher, although asset yields could continue to partly offset this until rates eventually fall. Net interest revenue is expected to bottom in the next quarter although some do not see this until early 2024.

There is some optimism that deposit betas, now in the 40s for most (a few over 50), may also be nearer a peak and that there is slower expansion in overall deposit costs monthly. There is also some indication that migration into interest-bearing buckets is slowing. Many banks were also highlighting reductions in brokered deposits and much lower FHLB reliance, as loan-to-deposit ratios remain relatively low. But, make no mistake, when rate cuts finally do emerge, margin compression will happen again.

3) A credit loss cycle of some magnitude is certain. Credit erosion is already visible, but it is still modest and considered to be simply normalizing. There is no discernible impact/damage yet seen from high interest rates per se. But this will come. Loan losses continue to be below “normal” despite some sporadic hits from shared national credits. But normal is a bit of an unknown variable for nonperformings and chargeoffs. Commercial real estate is the prime suspect as fixed rate lending begins repricing rather sharply. Office exposure is the obvious, greatest concern.

Wherever normal is, analysts are initially prone to overshoot potential loss estimates, as they did in 1989-90 when this sector became seriously overbuilt. At that time critics claimed there was a ten-year supply of office space, which turned out to be a far too negative assumption, but investors held to high anxiety in the early days of analyzing and predicting cumulative damage. Nonetheless, banks now uniformly claim that loss reserves incorporate a mild recession, even with an unemployment rate reaching 6%. This begs skepticism until we are further into the loss cycle.

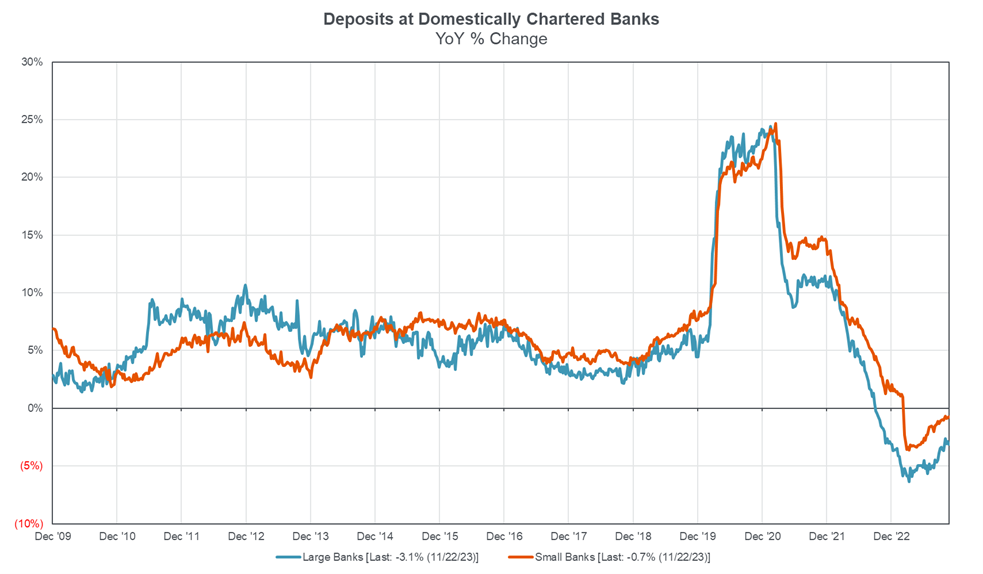

4) Deposit Franchise Challenge: After the March 2023 deposit crisis and subsequent outflows from the banking system, order was restored relatively quickly – with Fed help. However, deposits in the system were already declining post-COVID and continue to be negative on a year-over-year comparison (see the exhibit below.) The good news is that this decline has stabilized and seems to be in gradual reversal since May.

Weak loan demand and relatively low loan-to-deposit ratios remove some of the pressure on deposit funding, but bank managements need to rethink not only pricing and mix changes to their deposit business models but also diversification and stability measures, particularly among commercial accounts in this new era of electronically enabled flight that became dramatically apparent in March.

The largest banks are marginally lagging in deposit momentum and have been more volatile than for regional and community banks, the latter averaging a relatively steady $6 billion per week in net new deposits over the last six months – considerably better than in 2022 but only half that in 2021. Managements need also to be aware that the Bank Term Funding Program installed after the deposit crisis could cease in March 2024, and no new FDIC insurance modifications have surfaced.

5) Basel III Endgame Clarification: Banks will be flooding the regulatory community with commentary on the recently proposed rules. This may result in some rule modifications that will allow better calculation of the eventual capital impact. Early quantification of potential impact has merely reflected the likely increase in risk-weighted assets and the general ability to meet the higher standards within the minimum levels being assumed. Many managements are arguing that the impact will be ultimately offset in credit repricing, and some have taken the event as reason for holding up buybacks pending rule finalization.

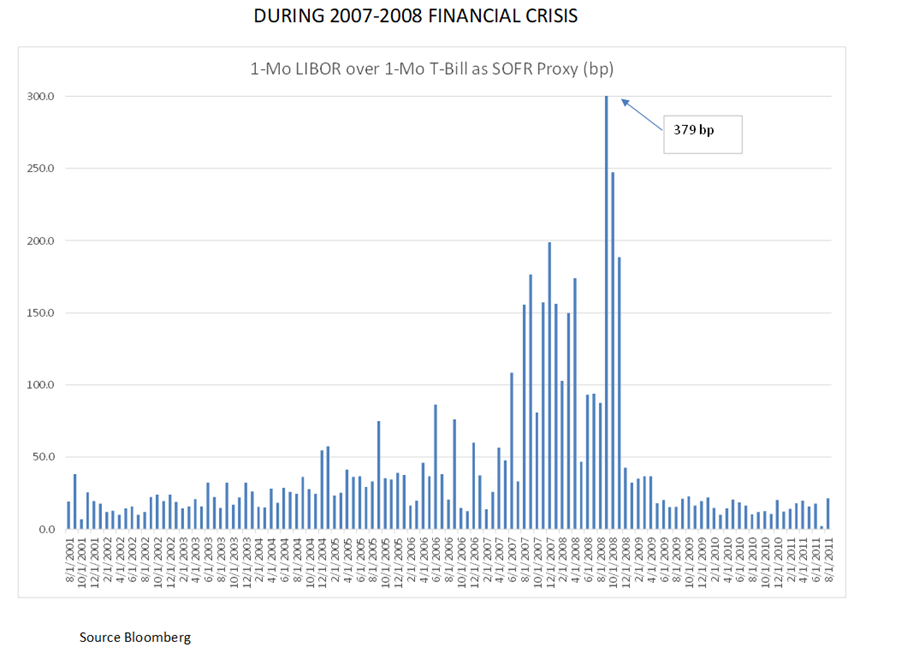

6) Rapid Adoption of SOFR for Bank Loan Pricing Adds Serious Risk: SOFR is rapidly proliferating in loan pricing following the demise in LIBOR. While SOFR may impeccably measure the risk-free rate of government funding, LIBOR, with its faults, at least measured the risk in funding bank credit, the far more relevant variable. They aren’t the same. And they can quickly become cyclically opposite.

In the event of any period of a flight-to-quality, which has a historic habit of recurring, government funding rates including SOFR will always drop sharply. This will occur as bank funding should instead be rising. Therefore, bank loan portfolios based on SOFR will sharply reprice down, whereas LIBOR always went in the opposite direction and rose. Gross loan margins would be quickly compressed, at a time when bank earnings are also being hammered by higher funding costs and higher loan losses. This would produce a “pro-cyclical” worsening in credit availability during an already stressed credit cycle.

Using a reconstruction of SOFR during the Great Financial Crisis, while LIBOR-based loan rates actually went up as they should, as that index was credit-sensitive, Treasury rates fell sharply. The gap between the two would have quickly widened to over 200 basis points, and briefly exceeded 300 basis points as shown in the exhibit below. The net interest margin for a SOFR-based commercial loan portfolio would have collapsed in half, if not more. This same perverse behavior again occurred during the onset of COVID in March 2020, when SOFR fell 122 basis points while LIBOR rose 20 basis points, a somewhat smaller gap which fortunately lasted for only two months, but nonetheless carried significant revenue damage.

Banks should either adopt a credit sensitive rate index to avoid another banking crisis or, at a minimum, return to prime rate loan pricing. While the prime rate has historically been tied to the Effective Fed Funds rate, it utilizes a movable spread above that rate – currently 325 basis points – leaving bank managements the ability to at least widen that spread during a crisis or any unanticipated rise in funding costs.