It’s 2024. Do you know what your overnight borrowing costs are?

For many regional and community banks, the answer is no – and poor regulatory guidance is a primary cause. After years of manipulation scandals, the LIBOR interest rate was thankfully officially discontinued on June 30, 2023. At last, financial institutions had an opportunity to assess their risk using an uncorrupted rate based on real transactions.

Yet just days later, IOSCO issued a statement on alternatives to LIBOR. Among its assertions was that credit-sensitive rates do not comply with international benchmark standards: “Absent modification, their use may threaten market integrity and financial stability.” Instead, SOFR – already used by many firms that had abandoned LIBOR – was identified as a less vulnerable rate, entrenching its position as the popular alternative.

This was an exceedingly poor outcome. Put simply, IOSCO’s conclusion was wrong. Whatever its virtues, SOFR reflects costs that are in many cases wholly irrelevant to the borrowing activity of regional and community banks – the engines that power Main Street economies throughout the US. It’s unfortunate that this momentous shift in the loan funding market was immediately met with a repudiation of credit-sensitive rates, which provide a much better reflection of the overnight borrowing costs of smaller institutions. With so many firms discouraged from using a benchmark that aligns with the nature of their business, the risk of widespread banking turmoil is significantly greater.

Why? Let’s break it down.

SOFR and Commercial Banks: A Square Peg for a Round Hole

The basic use case for interest rate benchmarks among regional and community banks is fairly straightforward. These institutions want to manage interest rate risk and maintain stable margins by charging a lending rate equal to a fixed spread over their borrowing costs. To meet their short-term liquidity needs, commercial banks fund themselves through a number of means: federal funds, certificates of deposit, commercial paper, etc. To accurately calculate risk, they must capture the cost of operating in these short-term wholesale funding markets.

These banks provide many services – they sustain small businesses, provide mortgages, support community infrastructure and more – but they typically do not make markets, nor do they provide leverage to hedge funds or other sophisticated investment managers. That is the realm of dealers. To finance both their large inventories and their secured lending activity, dealers typically maintain large positions in Treasury bonds and sell them on the repo market to meet short-term funding needs.

The problem with SOFR is that it reflects the cost of overnight dealer financing against Treasury collateral. It represents the secured borrowing rate used by dealers to provide leverage. This is wholly inadequate for the needs of commercial banks, which seldom hold large quantities of government securities. These banks borrow funds in unsecured markets, where creditworthiness is a far bigger consideration.

Commercial banks might be able to use SOFR to get a rough sense of their borrowing costs, but the margin for error shrinks amid market turbulence. As we saw last year with the implosion of Silicon Valley Bank, it only takes one bank miscalculating its risk exposure to precipitate a wave of failures and catastrophic losses. In addition, it’s unfortunate that at a time when community and regional businesses are facing significant pressure due to inflation and other macroeconomic factors, commercial banks have been discouraged from selecting a benchmark or combination of benchmarks that reflect their business model.

The Value of Credit-Sensitivity: A COVID Case Study

A new paper by Marco Macchiavelli – a finance professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and a former economist on the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors – illustrates how a credit-sensitive benchmark interest rate can benefit commercial banks during times of market stress.

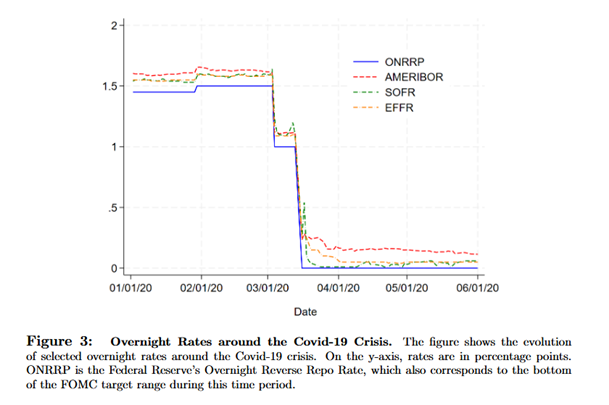

In the early days of the COVID-19 crisis, interest rates fell dramatically between March and April 2020 before stabilizing later in the spring and summer. However, there were days when SOFR moved in the opposite direction of bank funding costs. The spreads between SOFR and its credit-sensitive counterparts is usually fairly small (though still significant enough to invite risk), but at the outset of the pandemic, they widened to as many as 23 basis points.

The result? Commercial banks indexing their credit lines to SOFR may have received lower returns while facing higher borrowing costs. This mismatch would have led to negative interest rate margins, inviting significant risk during a period when economic turmoil was already widespread. The pandemic was a time when Americans needed their regional and community banks to be more vigilant than ever; sole reliance on SOFR would have undercut this mandate.

Yet sole reliance on SOFR is effectively what IOSCO called for in its statement last year. With LIBOR gone, there is no longer a rate that meets IOSCO’s standards while capturing the marginal funding costs of commercial banks. SOFR may be less prone to manipulation, but it simply isn’t relevant to a huge swath of financial institutions, at least not entirely. We’ve taken the shortcomings of one benchmark and replaced them with the shortcomings of another.

What these banks need is a credit-sensitive rate based on real transactions. As the Macchiavelli paper explains, they’re out there – but the market needs to feel confident in adopting them. I urge IOSCO to reconsider its position and reexamine the benefits of credit-sensitive rates. Until then, I’ll continue to beat this drum – because a more stable, efficient lending landscape is worth fighting for.